Bootsnap and Spring, Understanding rails boottime optimisations

Being the default the gem file entries in a rails project, you may have encountered spring and bootsnap. Here we are going through how they work and how they can improve boot time of your applications and why you get some weird errors in the app(Looking at you Spring).

Before diving into details, let’s go through some fundamentals to understand things better. Traditionally there were two kinds of languages, Compiled languages and interpreted languages. Compiled languages convert the code into binary format and that binary gets executed as the program. C, C++, Java etc are examples for this pattern. Another set of languages which were primarily designed for scripting read individual lines in the code and converted to machine instructions on runtime.

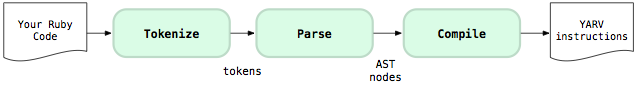

With ruby 1.9, a new virtual machine replaced the interpreter in ruby which was called Mat’s Ruby Interpreter(MRI). With a new virtual machine. Here instead of directly executing the code, ruby code will be converted to an intermediate representation called instruction sequence and the YARV virtual machine will execute them.

You can refer to the following diagram for reference.

Credit: Ruby under a microscope

There are also bulletin tools to inspect what is happening in the process, let’s check what happens for a 3 line code.

require 'ripper'

require 'pp'

code = <<CODE

def add(x, y)

x + y

end

CODE

Let’s split the code into tokens using ripper utility

irb(main):043:0> Ripper.tokenize code

=> ["def", " ", "add", "(", "x", ",", " ", "y", ")", "\n", "x", " ", "+", " ", "y", "\n", "end", "\n"]

And see the parsed form using ripper sexp

irb(main):042:0> pp Ripper.sexp(code)

[:program,

[[:def,

[:@ident, "add", [1, 4]],

[:paren,

[:params,

[[:@ident, "x", [1, 8]], [:@ident, "y", [1, 11]]],

nil,

nil,

nil,

nil,

nil,

nil]],

[:bodystmt,

[[:binary,

[:var_ref, [:@ident, "x", [2, 0]]],

:+,

[:var_ref, [:@ident, "y", [2, 4]]]]],

nil,

nil,

We can also take look at how the Instruction sequence(yarv code) looks like

irb(main):052:0> puts RubyVM::InstructionSequence.compile(code).disasm

== disasm: #<ISeq:<compiled>@<compiled>:1 (1,0)-(3,3)> (catch: FALSE)

0000 definemethod :add, add ( 1)[Li]

0003 putobject :add

0005 leave

== disasm: #<ISeq:add@<compiled>:1 (1,0)-(3,3)> (catch: FALSE)

local table (size: 2, argc: 2 [opts: 0, rest: -1, post: 0, block: -1, kw: -1@-1, kwrest: -1])

[ 2] x@0<Arg> [ 1] y@1<Arg>

0000 getlocal_WC_0 x@0 ( 2)[LiCa]

0002 getlocal_WC_0 y@1

0004 opt_plus <calldata!mid:+, argc:1, ARGS_SIMPLE>

0006 leave ( 3)[Re]

=> nil

Explaining the terms in the parsed and compiled code is beyond the scope of this blog post, and I recommend reading Ruby Under a Microscope.

Newer versions of ruby also allows us to compile the code to binary and execute them later. it is experimental and platform dependent.

? cat example.rb

number = 23

puts number + 23

? ruby -e "File.write('example.bin',RubyVM::InstructionSequence.compile_file('example.rb')

.to_binary)"

? cat example.bin

YARB@

?x86_64-darwin18%?#?%?gw

numberE+Eexampleputs?????????%

irb(main):018:0> RubyVM::InstructionSequence.load_from_binary(File.read('example.bin')).eval

46

That is it for the ruby compilation process for now. Now let’s how the ruby’s require method works.

Contrary to what I thought initially, require is not a keyword in ruby, it is a method from ruby’s Kernal module.

Let’s look at the overly simplified version of require method for our context.

def require(file_name)

eval File.read(filename)

end

Two main issues with this implementation are

- Requiring same file again will load the file again

- Only absolute paths are supported

We can fix these issues in the following ways

$LOADED_FEATURES = []

def require(filename)

return false if $LOADED_FEATURES.include?(filename)

eval File.read(filename)

$LOADED_FEATURES << filename

end

$LOAD_PATH = []

#$LOAD_PATH = += gems_path + stdlib path + application code paths

def require(filename)

full_path = $LOAD_PATH.take do |path|

File.exist?(File.join(path, filename))

end

eval File.read(full_path)

end

While above code snippets are dummy implementations, Ruby actually uses the constants $LOADED_FEATURES and $LOAD_PATH for the same use case. Here is a stat from one of our app for reference

irb(main):054:0> $LOADED_FEATURES.count

=> 6552

irb(main):058:0> $LOAD_PATH.count

=> 779

Another important method we need to recall is the fork system call in POSIX systems. fork allows the OS to create a new process as the child process with the same memory space. Modern hardware architectures like x86 allows the OS to optimise the fork with a mechanism called copy on write. In short it is very cheap to create a forked process of an app than loading that app from scratch.

Now let’s look at the gems from the title.

Spring is a rails only tool to speedup development and test environments. It creates your app process in the background for development and test environments and acts as a server. When you run a process like bundle exec rails server or bundle exec rspec it sends the data like command, ENV values, arguments etc to spring server, and spring server will fork the server process and run the task.

Since the server process already loaded the app, the loading time of the app will be negligible and your task will run faster.

But when the code changes, the server process needs to update and it may fail due to various reasons, like adding new directories. That is why you ended up having to run spring stop manually or restart the system to make the application behave as expected.

The serve method in Spring is provided as reference. You can see zipping io values, fetching arguments, env etc from client, forking the new process etc in the below snippet.

def serve(client)

log "got client"

manager.puts

_stdout, stderr, _stdin = streams = 3.times.map { client.recv_io }

[STDOUT, STDERR, STDIN].zip(streams).each { |a, b| a.reopen(b) }

preload unless preloaded?

args, env = JSON.load(client.read(client.gets.to_i)).values_at("args", "env")

command = Spring.command(args.shift)

connect_database

setup command

if Rails.application.reloaders.any?(&:updated?)

Rails.application.reloader.reload!

end

pid = fork {

Process.setsid

IGNORE_SIGNALS.each { |sig| trap(sig, "DEFAULT") }

trap("TERM", "DEFAULT")

unless Spring.quiet

STDERR.puts "Running via Spring preloader in process #{Process.pid}"

if Rails.env.production?

STDERR.puts "WARNING: Spring is running in production. To fix " \

"this make sure the spring gem is only present " \

"in `development` and `test` groups in your Gemfile " \

"and make sure you always use " \

"`bundle install --without development test` in production"

end

end

ARGV.replace(args)

$0 = command.exec_name

# Delete all env vars which are unchanged from before Spring started

original_env.each { |k, v| ENV.delete k if ENV[k] == v }

# Load in the current env vars, except those which *were* changed when Spring started

env.each { |k, v| ENV[k] ||= v }

# requiring is faster, so if config.cache_classes was true in

# the environment's config file, then we can respect that from

# here on as we no longer need constant reloading.

if @original_cache_classes

ActiveSupport::Dependencies.mechanism = :require

Rails.application.config.cache_classes = true

end

connect_database

srand

invoke_after_fork_callbacks

shush_backtraces

command.call

}

disconnect_database

log "forked #{pid}"

manager.puts pid

wait pid, streams, client

rescue Exception => e

log "exception: #{e}"

manager.puts unless pid

if streams && !e.is_a?(SystemExit)

print_exception(stderr, e)

streams.each(&:close)

end

client.puts(1) if pid

client.close

ensure

# Redirect STDOUT and STDERR to prevent from keeping the original FDs

# (i.e. to prevent `spring rake -T | grep db` from hanging forever),

# even when exception is raised before forking (i.e. preloading).

reset_streams

end

Bootsnap is a gem released by shopify by extracting boot time improvements they made in their app. We can categorise them into two parts

Path prescanningPermalink

- Kernel#require and Kernel#load are modified to eliminate $LOAD_PATH scans

- ActiveSupport::Dependencies.{autoloadable_module?,load_missing_constant,depend_on} are overridden to eliminate scans of ActiveSupport::Dependencies.autoload_paths.

Compilation CachingPermalink

- RubyVM::InstructionSequence.load_iseq is implemented to cache the result of Ruby bytecode compilation

- YAML.load_file is modified to cache the result of loading a YAML object in MessagePack format (or Marshal, if the message uses types unsupported by MessagePack)

If you look at the pseudo code above to demonstrate the LOAD_PATH behaviour, you will see that we need to check file existence every time we do a require, which is an io operation and not very cheap to perform. What if we can do something like this?

def require(filename)

if $CACHED_PATH[file_name]

full_path = $CACHED_PATH[filename]

else

full_path = $LOAD_PATH.take do |path|

File.exist?(File.join(path, filename))

end

end

eval File.read(full_path)

end

load path for a library is not something that changes very often, especially for gem paths and standard library paths, bootsnap caches them to save redundant file checks. Not that cache duration and expiration vary with files, so caching them in a constant won’t work. CACHED_PATH is just for reference and not used by the gem.

Another important optimization by bootsnap is the compilation cache. We covered the ruby compilation process in the beginning and saw that every single file needed to go through the compilation process every single time they got called. Bootsnap addresses this by caching yarv code(instruction sequence) and compiling the code only if the code changes.

There are also other optimised YAML loading by caching in an optimised format. overall Bootsnap gives impressive benefits as it works on production as well. We got about 30% reduction in boottime for our production ecommerce app.

Note: This was originaly presented in internal tech talk in Sephora and made some tweaks to the content for wider audience.

Comments